2007年VOA标准英语-Vietnamese Art Flourishes Despite Censorship(在线收听)

Hanoi

12 February 2007

In January, police in Hanoi ordered a Vietnamese artist to remove his installation - a giant diaper, with a lining composed of hundreds of police shirt pockets - from a German-sponsored exhibition. Although rules on self-expression have loosened somewhat over the past several years, the flourishing Vietnamese art scene still faces government censorship, as Matt Steinglass reports from Hanoi.

When

|

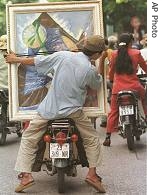

| A worker hangs onto an abstract painting while transporting it on the back of a motor bike through the streets of Hanoi (File) |

"It was a very ironic piece about corruption," he said. "It's a diaper, a huge diaper, made in the form of a sofa, put together out of uniform pockets. And the comment of the artist is, the absorbency is unlimited."

The absorbent pockets, which Tan stitched himself, were made to look like those on police uniforms.

In Vietnam, where the government limits free expression, a comment on police corruption is risky. The exhibit went up on January 10. The police response came soon afterward.

"Two days later I got a call, I was in Saigon, I got a call: the police have asked us to remove these two pieces," he said.

The authorities wanted both Vietnamese artists' pieces taken down, saying that the institute had only asked for permission to show German works. To avoid trouble, the artists agreed.

Truong Tan, 42, a former teacher at Vietnam's Academy of Fine Arts, lived in France for several years before returning to Vietnam in 2004.

He says he moved to France because he was frustrated with censorship here. To show his work in official galleries, he would have had to submit it first to the censors.

"I don't want to show them, and then say, give me permission," he said. "Because my work is free. And they're never thinking artists must be free. Here, they always think we are freedom, freedom, open, open. But for art it's not."

Tan's giant diaper now sits in his workshop. Tan says it is about lack of transparency, and a comment on Vietnam's new tourism slogan, "The Hidden Charm".

"I want people see inside the pockets of the leaders peoples in my country," said Tan. "What is it inside? The title of my work is 'Hidden Beauty'. At this moment Vietnamese always say 'hidden charm, hidden beauty'. I don't know, what is inside?"

Censorship is not immediately apparent on visiting an art gallery. Vietnamese artists are free to address personal themes, and even are allowed to make subtle social criticisms.

But the Ministry of Culture must approve any art project or exhibition, which slows the art scene down and frustrates international contacts.

Marcus Mitchell is one of several young Americans behind Campus, a new art space that has become a center of the Hanoi cultural scene.

Mitchell says a major problem for Vietnamese artists is that censorship isolates them from the contemporary art world. He says young Vietnamese are often unaware of how isolated they are.

"This generation thinks they're tapped into contemporary art globally, because they're surfing on the Web and they're looking at magazines," said Mitchell. "But all they get, and it's really frustrating, you kind of get like knockoff clothing - like imitation Nike. It's purely superficial."

Vietnamese art sells extremely well these days, at galleries in Hong Kong, Los Angeles and New York. Mitchell says the reason is simple.

"Novelty. Asia's hot, and the market in China's completely bloated right now, and everybody's looking for the next big thing," he said.

Sitting in the garden of his Hanoi house, Truong Tan says he thinks the censorship cannot last forever.

"I think it's better, but they must open more," he said. "Because they must think, the ideas of people must change. And they change."

The Goethe Institute's Augustin says Vietnam must move beyond what he calls "ridiculous, petty censorship." For foreign observers and Vietnamese artists, the reaction to Tan's giant diaper is a sign that change is not going to come soo