VOA慢速英语-THE MAKING OF A NATION - American History Series: Je(在线收听)

The opposition Federalist Party warned that Thomas Jefferson’s financial program would crush the nation. Transcript of radio broadcast:

11 June 2008

ANNOUNCER:

Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION – an American history series in VOA Special English.

By eighteen hundred and one, Thomas Jefferson of Virginia had already done much for his country. He wrote the Declaration of Independence in seventeen seventy-six. He served as America's first ambassador to France and its first secretary of state. Now he would govern the nation.

This week in our series, Maurice Joyce and Richard Rael continue the story of America's third president.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

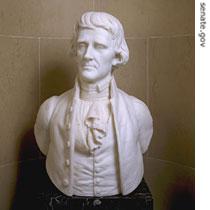

|

| Thomas Jefferson by Moses Jacob Ezekiel |

Thomas Jefferson was happy and hopeful as he took office. His new political party, the Republicans, had defeated the older Federalist Party. The Federalists had controlled the government for twelve years.

America's first president, George Washington, was not a Federalist. But Federalists controlled the cabinet and the Congress during Washington's two terms. America's second president, John Adams, was a Federalist. So the party continued its control during his term.

VOICE ONE:

The Federalists and the Republicans held very different opinions about how to govern the nation. Yet the change in power from one party to the other took place peacefully.

Thomas Jefferson recognized the importance of this fact. He said: "What we have done in this country is all new. The force of public opinion is new. But the most important and pleasing newness is that we have changed our government without violence. This shows a strength of American character that will give long life to our republic."

VOICE TWO:

President Jefferson wanted to work with Federalists for the good of the nation. But he chose no Federalists for his cabinet. All the cabinet officers were strong Republicans. All were loyal to Thomas Jefferson.

James Madison of Virginia was secretary of state; Albert Gallatin of Pennsylvania, secretary of the treasury; General Henry Dearborn of New Hampshire, secretary of war; Robert Smith of Maryland, secretary of the Navy; and Levi Lincoln of Massachusetts, attorney general.

VOICE ONE:

For other government positions, Jefferson decided to take a middle road. He would remove all officials appointed by former President John Adams during his lame duck period. That was the time after Jefferson won the election, but before he took office. He also would remove all officials found guilty of dishonesty.

He said: "Federalists in government positions have nothing to fear if they have acted honestly and with justice. Those who have acted badly must go. As for the men I appoint to office, they must be of the highest character. I will accept no others."

VOICE TWO:

Federalist leaders denounced Jefferson's policy. They thought all Federalists should keep their government jobs. Many Republican leaders denounced Jefferson, too. They thought no Federalist should have a government job. The president was caught between the two groups.

He finally answered his critics. "Shouts and screams from Federalists or Republicans," he said, "will not force me to remove one more official, or one less. I will do what I think is right and just."

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

|

| Ivory note pages owned by Thomas Jefferson |

Once President Jefferson formed his cabinet, he began planning the policies of his administration. His two closest advisers were Secretary of State Madison and Treasury Secretary Gallatin. First, they discussed financial policy.

They agreed that the government must stop spending as much money as it did under former president Adams. So, government departments would get less money. They also agreed that the government must pay its debts as quickly as possible.

The government owed millions of dollars. Each year, the debt grew larger because of the interest on these loans.

Albert Gallatin said: "We must have a strong policy. The debt must be paid. If we do not do this, our children, our grandchildren, and many generations to come will have to pay for our mistakes."

VOICE TWO:

President Jefferson wanted to pay the government debt. He also wanted to cut taxes on the production and sale of some products, such as whiskey and tobacco. He hoped the government could get all the money it needed from import taxes and from the sale of public lands.

Jefferson began saving money by ending unnecessary jobs in the executive branch. He reduced the number of American ambassadors. He dismissed all tax inspectors.

Congress would have to take the next steps. "Most government offices," Jefferson said, "were created by laws of Congress. Congress alone must act on these positions. The citizens of the United States have paid for these jobs with their taxes. It is not right or just for the government to take more than it needs from the people."

Jefferson especially wanted Congress to reduce the judicial branch. He hoped to dismiss all the Federalist judges former President Adams appointed during his last days in office. These men were known as "midnight judges."

VOICE ONE:

The Federalists were furious. They accused Jefferson of trying to destroy the courts. They warned that his financial program would crush the nation. They declared there would be anarchy if Federalist officials were dismissed.

Most people, however, were happy. They liked what Jefferson said. They especially liked his plan to cut taxes.

|

| Alexander Hamilton |

Jefferson's biggest critic was his long-time political opponent, Alexander Hamilton. Hamilton had served as the nation's first treasury secretary. Now, he was a private lawyer in New York City. He published his criticism of Jefferson in a newspaper he started, the New York Evening Post.

VOICE TWO:

While the public debated Jefferson's policies, the Congress debated his proposal to reduce the number of federal courts. Federalist congressmen claimed that the president was trying to interfere with the judiciary. This, they said, violated the Constitution.

Republican congressmen argued that the Constitution gave Congress the power to create courts and to close them. They said the former administration had no right to appoint the so-called "midnight judges."

The Republicans won the argument. Congress approved President Jefferson's proposal on the courts.

VOICE ONE:

Next, Congress debated the president's proposal to cut taxes. Federalists said it was dangerous for the government to depend mainly on import taxes. They said such a policy would lead to smuggling. People would try to bring goods into the United States secretly, without paying taxes on them.

Federalists also said that if the United States cut taxes, it would not have enough money to pay its debts. Then no one would want to invest in the United States again.

VOICE TWO:

Republicans said they were not afraid of smugglers. The danger, they said, would come from taxing the American people. There was no need for production and sales taxes. And, they said, the American people knew it. The Republicans also said they were sure the government would have enough money to pay its debts.

The Republicans won this legislative fight, too. Both the Senate and the House of Representatives voted to approve the president's plan to cut taxes.

VOICE ONE:

Congress then turned to other business. But the question of the midnight judges would not die. In fact, the Supreme Court would hear the case of one of those judges. Its decision gave the court an extremely important power, which it still uses today.

That will be our story next week.

(MUSIC)

ANNOUNCER:

Our program was written by Christine Johnson and Harold Braverman. The narrators were Maurice Joyce and Richard Rael. Join us each week for THE MAKING OF A NATION -- an American history series in VOA Special English. Transcripts, podcasts and MP3s of our programs can be found at voaspecialenglish.com.