VOA慢速英语-THE MAKING OF A NATION - American History Series: Je(在线收听)

''For a time, I think the embargo is less evil than war,'' the outgoing president said. Finally he accepted a compromise -- trade, except with Britain and France. Transcript of radio broadcast:

16 July 2008

ANNOUNCER:

Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION – American history in VOA Special English.

This week in our series, Steve Ember and Shirley Griffith have the story of Thomas Jefferson's final acts as president, and the election of James Madison.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

|

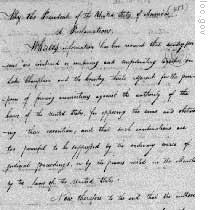

| A proclamation written by Thomas Jefferson in April 1808 about the embargo laws |

In the closing days of eighteen-oh-seven, President Thomas Jefferson signed a bill banning all trade with Europe. No ships could enter the United States, and no ships could leave. The purpose of the trade ban was to keep America out of the war between Britain and France.

Jefferson acted to protect American traders, ship owners and sailors. Yet those were the people who protested loudest against the ban. They were willing to take the chance of having Britain or France seize their ship and goods. They could make no money without trade.

VOICE ONE:

The situation quickly turned into a political battle between Jefferson's party, the Republicans, and the opposition Federalists.

Federalist newspapers attacked Jefferson. They charged that he supported the trade ban to help Napoleon Bonaparte. They called him a tool of France.

One Federalist senator wrote a pamphlet against the trade ban. He urged northeastern states to refuse to enforce it. Then he went even further. He met secretly with the British official sent to Washington to discuss the situation. He told the British official that President Jefferson would be forced out of office because of the trade ban.

The Federalists tried hard to get Congress to end the ban. But they were not successful.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

|

| Detail of the cartoon "Intercourse or Impartial Dealings" in which President Jefferson is being held up for money by Napoleon of France and King George of Britain. The image makes fun of Jefferson's embargo policy. |

President Jefferson did not believe that trade bans -- embargoes -- were the best way to settle America's problems with other nations. But at the time, he thought an embargo was the only way to deal with Britain and France, short of war. And he did not want war.

Jefferson's economic policies had brought much progress during his two terms as president. He had been able to pay much of the national debt, and still reduce taxes. He also had begun several projects to improve communication and transportation throughout the country. He was afraid that a war would destroy everything he had done.

VOICE ONE:

Jefferson simply wished to give the trade embargo a fair chance. "For a time," he wrote, "I think the embargo is less evil than war. But after a time, this will not be so. If the war should continue in Europe, and if Britain and France continue to act against us, then it will be for Congress to say if war would not be better than the embargo."

Jefferson hoped that the loss of American trade would force Britain and France to change their policies toward the United States. And he hoped the change would come quickly, for he knew the American people would not accept a long ban on trade.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

A British traveler visiting New York City described what the embargo had done. He wrote: "The port is full of ships. But all of them are closed. Only a few sailors can be seen. Many of the counting houses are closed. The coffee houses are almost empty. The streets near the water are almost deserted. Grass has begun to grow upon the docks."

VOICE ONE:

America's northern industrial states felt the loss of trade most strongly. But the agricultural South also was affected. Rich southern farmers and planters suddenly found themselves poor.

Tobacco was one of their major crops. And Britain bought more American tobacco than any other country. Its price fell so low because of the embargo that it had almost no value. The price of wheat fell from two dollars a bushel to seven cents a bushel. Good farmland dropped in value until it was worth almost nothing. Opposition to the embargo was growing.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

|

| Albert Gallatin was treasury secretary from 1801-1814, under Jefferson and then President James Madison |

Opposition was strongest in the Northeast. Ship owners and traders there believed that the embargo was wrong. They continued to export goods secretly.

Some traders began sending goods over land to Canada. From there, the goods were sent on to Britain. Congress passed a law against this kind of trade. But the shipments did not stop. Too many people were willing to violate the law for the large amounts of money they could make by trading secretly with Britain.

By August, eighteen-oh-eight, Treasury Secretary Albert Gallatin had lost all hope that the embargo would be successful. Gallatin told President Jefferson: "The embargo is now defeated by open violations, by ships sailing without permission of any kind."

VOICE ONE:

Another of Jefferson's supporters gave the president this advice: "If the trade ban could be enforced, and if the people would accept it, then I am sure it would be the wisest course. But if it cannot be enforced completely, and if the people will not accept it, then it will not answer its purpose. And it should not be continued."

VOICE TWO:

|

| President Thomas Jefferson |

Jefferson, however, was not ready to give up his plan. In his last State of the Union message to Congress, he painted a bright picture of the nation.

He reported that American industry was making progress. Many goods which had been imported before the embargo were now being made at home. He said almost all of the national debt had been paid. And he said more than one hundred gunboats had been built -- enough, he declared, to defend the country.

Jefferson said nothing about opposition to the embargo. Nor did he talk of the serious economic problems caused by it. He said only that Britain and France still refused to honor American neutrality, and so the embargo must continue.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

The rest of the nation was not so sure. Congress began debating a number of proposals to either lift or amend the embargo. And the opposition Federalist Party used the issue to increase its strength in northeastern states. Eighteen-oh-eight was, after all, a presidential election year.

VOICE TWO:

Thomas Jefferson had served two four-year terms as president. No law prevented him from running again. But Jefferson had decided years before that a man should be limited to two terms as president.

Without such a limit, Jefferson believed, a powerful man might be able to keep the position for as long as he wished. George Washington had served two terms, and then retired. Jefferson would do the same.

VOICE ONE:

Three members of Jefferson's Republican Party wanted to be president. One was James Madison, the secretary of state. The second was James Monroe, who had served as a special assistant to the president. The third was George Clinton, who was vice president during Jefferson's second term.

The Republican Party chose Madison as its candidate for president. It chose Clinton as its candidate for vice president. The Federalist Party named the same candidates it had chosen four years earlier: Charles Cotesworth Pinckney for president, and Rufus King for vice president.

VOICE TWO:

The Federalists were sure of victory in the election. They thought that Jefferson's embargo on trade had angered the people and turned them away from the Republican Party. Even some Republicans felt the election could go very badly for their party.

But Jefferson remained calm. He believed that most Americans understood what he was trying to do with the embargo. And he believed they would vote for his party's candidate. Jefferson was right. Madison was elected.

VOICE ONE:

As we said earlier, Congress was trying to resolve the issue of the embargo before Jefferson left office.

In the first months of eighteen-oh-nine, it finally approved a bill. The bill lifted the ban on trade with all European countries except Britain and France.

Jefferson had hoped to continue the embargo a little longer and with more powers to enforce it. He was not satisfied with the final bill. But he signed it anyway on March first. Three days later, the fifteen-month-old embargo was dead. And the United States had a new president.

That will be our story next week.

(MUSIC)

ANNOUNCER:

Our program was written by Frank Beardsley. The narrators were Steve Ember and Shirley Griffith. Join us each week for THE MAKING OF A NATION – an American history series in VOA Special English. Transcripts, podcasts and MP3s of our programs are at voaspecialenglish.com.

__

This is program #42 of THE MAKING OF A NATION