-

(单词翻译:双击或拖选)

He helped change racial separation laws in America. Transcript1 of radio broadcast:

26 July 2008

VOICE ONE:

This is Gwen Outen.

VOICE TWO:

And this is Doug Johnson with People in America in VOA Special English. Every week we tell about a person who was important in the history of the United States. Today we tell about a man who helped change the racial separation laws of America, Thurgood Marshall.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

Thurgood Marshall was born a free man. But the father of his grandfather was a slave. He had lived in what was the Congo area of Africa. A man from the eastern American city of Baltimore, Maryland, brought him to the United States. He later set him free.

|

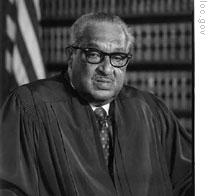

| Thurgood Marshall |

Thurgood Marshall was born in Baltimore on July second, nineteen-oh-eight. In that city, and in many other parts of the United States at that time, black people were separated from white people by law. Black children did not go to school with white children. Black people lived only in areas where other blacks lived.

VOICE TWO:

Over the years, Thurgood Marshall became a very good storyteller. He told stories about himself, or about places he had visited. Often, the stories were funny. But most also had a serious message.

One story was about being in trouble with his teachers when he was a boy in Baltimore.

Mister2 Marshall said one of his teachers punished him by sending him to the room where the school's heating3 equipment was kept. There he was told to read and remember the words of the Constitution of the United States.

The Constitution is a long document. Thurgood Marshall said he read all of it -- more than once -- and learned4 to remember most of it.

He said this schoolboy punishment gave him a life-long respect for the Constitution. As he grew older, he began to think about the Constitution's guarantees of freedom. Those guarantees, he believed, should be for people of all races, not just for white people.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

Thurgood Marshall attended Lincoln University in the state of Pennsylvania. He completed his studies, with honors6, in nineteen thirty. He wanted to go to law school at the University of Maryland. But officials at that school refused to let him attend because he was black. So he went to law school at Howard University in Washington D.C. Howard University was a school for African Americans. Thurgood Marshall graduated first in his class.

After completing his law studies, he accepted the case of a young black man who wanted to become a lawyer, too. The young man wanted to attend the University of Maryland law school. It was the same school that had refused to admit Thurgood Marshall. Again, the school refused to let a black man become a student. So, Mister Marshall took legal action. He won the case. The young black man was permitted to attend the university's law school.

Thurgood Marshall would go on to win many more cases dealing7 with racial separation laws. And years later, the University of Maryland would name its law library in his honor5.

VOICE TWO:

Thurgood Marshall was a very good lawyer. The people he represented in court were black and poor. He never earned much money. But his name soon became well known. The National Association8 for the Advancement9 of Colored People offered him a job. He went to work as one of its legal representatives.

In time, he became the organization's chief legal representative. He traveled across the United States. He fought against racial separation laws. He also defended black people who were charged with a crime, but who did not have the money to pay for legal help.

Many of those cases reached America's highest court, the Supreme10 Court of the United States. During his life as a lawyer, Thurgood Marshall argued cases before the Supreme Court more than thirty times. He lost only a few cases. Slowly, the laws of racial separation in America began to change. Many of those changes were the result of the work of Thurgood Marshall.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

Legal experts say that Thurgood Marshall's most important case was the one known as "Brown versus11 Board of Education." The case involved the city of Topeka in the middle western state of Kansas.

A law there said that having separate schools for black students and white students was legal, if the schools were the same. It was the idea of "separate but equal". But the schools were not equal. White children received a better education than black children.

Thurgood Marshall agreed to argue the case before the Supreme Court. When newspapers reported this, he began getting messages threatening him with death.

Other civil rights lawyers said he was moving too quickly. They said a defeat in the Brown case would greatly damage the cause of civil rights. They told him to wait, to move more carefully and slowly.

VOICE TWO:

Thurgood Marshall did not listen to the threats against his life. And he did not listen to those who said he should move more slowly. The Supreme Court heard the case in nineteen fifty-four. Mister Marshall said it was a violation12 of the Constitution to separate people because of their race.

So, he argued, the racially separated schools in Topeka, Kansas, were illegal. He added that nothing could be equal in racially separated schools.

One Supreme Court justice asked him to explain what he meant by the word equal. He answered: "Equal means getting the same thing, at the same time, and in the same place." The Supreme Court agreed. It ruled that no one could be rejected from a school in Topeka because of race.

VOICE ONE:

The case of "Brown versus Board of Education" provided13 the basis for other court decisions. It helped destroy the terrible wall of legal racial separation throughout the United States. Some people say it is the most important Supreme Court decision of the twentieth century.

That decision was the beginning of years of legal battles against racial separation in America's schools. It also sent a message to the people of the nation that black Americans had the same rights as white Americans. Many African Americans said Mister Marshall's victory in nineteen fifty-four changed their lives and their futures14.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

In nineteen sixty-one, President John Kennedy named Thurgood Marshall to be a judge of a federal15 appeals court. During his years on that court, Judge Marshall wrote more than one hundred opinions on different legal issues. Several of his opinions from those days have been approved as law by a majority of the Supreme Court.

|

| Justice Marshall served on the Supreme Court for 24 years |

In nineteen sixty-seven, President Lyndon Johnson nominated16 Thurgood Marshall to the Supreme Court. President Johnson said the nomination17 was the right thing to do, and the right time to do it. Thurgood Marshall became the first black person to serve as a Supreme Court Justice. He served for twenty-four years.

Justice Marshall wrote opinions about legal representation18 in America's criminal justice system. He said everyone has the right to be represented by a good lawyer, no matter how guilty they may be.

In his last years on the Supreme Court, he often voted against the majority of the more conservative19 members. Justice Marshall always voted in dissent20 in cases in which the majority voted that a death sentence was legal. He said no one should be put to death for any reason.

VOICE ONE:

In nineteen ninety-one, Thurgood Marshall announced that he would retire from the Supreme Court. Some reports said he no longer wanted to fight against the conservative majority of the court. At a news conference, a reporter asked him why he was retiring. Justice Marshall looked at the man and said, simply: "I am getting old and coming apart."

Another reporter asked Justice Marshall how he would like to be remembered. He sat quietly for a moment. Then Thurgood Marshall said: "I want to be remembered for doing the best I could with what I had."

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

This program was written by Paul Thompson. It was produced by Lawan Davis. This is Doug Johnson.

VOICE ONE:

And this is Gwen Outen. Listen again next week for People in America in VOA Special English.

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

transcript

|

|

| n.抄本,誊本,副本,肄业证书 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

mister

|

|

| n.(略作Mr.全称很少用于书面)先生 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

heating

|

|

| n.加热,供暖,暖气装置;adj.加热的,供暖的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

learned

|

|

| adj.有学问的,博学的;learn的过去式和过去分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

honor

|

|

| n.光荣;敬意;荣幸;vt.给…以荣誉;尊敬 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

honors

|

|

| n.礼仪;荣典;礼节; 大学荣誉学位;大学优等成绩;尊敬( honor的名词复数 );敬意;荣誉;光荣 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

dealing

|

|

| n.经商方法,待人态度 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

association

|

|

| n.联盟,协会,社团;交往,联合;联想 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

advancement

|

|

| n.前进,促进,提升 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

supreme

|

|

| adj.极度的,最重要的;至高的,最高的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

versus

|

|

| prep.以…为对手,对;与…相比之下 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

violation

|

|

| n.违反(行为),违背(行为),侵犯 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

provided

|

|

| conj.假如,若是;adj.预备好的,由...供给的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

futures

|

|

| n.期货,期货交易 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

federal

|

|

| adj.联盟的;联邦的;(美国)联邦政府的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

nominated

|

|

| adj.被提名的,被任命的 动词nominate的过去式和过去分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

nomination

|

|

| n.提名,任命,提名权 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

representation

|

|

| n.表现某人(或某事物)的东西,图画,雕塑 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

conservative

|

|

| adj.保守的,守旧的;n.保守的人,保守派 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

dissent

|

|

| n./v.不同意,持异议 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|