-

(单词翻译:双击或拖选)

Dakar

14 January 2007

The collapse1 of a diamond pit mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo earlier this month, in which 15 people were reported killed, has highlighted the dangers of primitive2, open pit mining. Phuong Tran reports from VOA's West and Central Africa bureau on the debate over how to control this unregulated sector3, which is one of the few ways for people to make a living in the impoverished4 region.

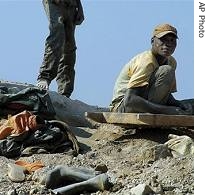

Miners handle stones on a hilltop of Mbola mines in Democratic Republic of Congo (File photo)

Industry experts say poverty and corruption5 contribute to the persistence6 of unregulated mining with little oversight7 and few safety measures.

Diamond consultant8 Chaim Even-Zohar estimates there are up to one-million Congolese informal miners and another nine-million people who depend on their incomes.

"What we see is that poor people, diggers who are not very literate9, not very educated, that believe that the diamonds will raise them out of poverty," said Zohar.

But, Zohar says, miners find they are not the ones making the money.

"In most places, you get a semi-slave situation, where investors10 - call them supervisors11, call them traders, they call them supporters in most countries - will put a gang together and give them a little bit [of ] money in advance, and they have to work for him, because they are indebted to him," added Zohar.

Efforts to regulate the informal mining sector in the Democratic Republic of Congo date back several years. A 2002 regulation requires inspections12 of mines, and licensing13 of diggers. A 2003 presidential decree created cooperatives of informal miners who receive training, small loans and equipment.

But officials have said that both efforts face funding problems.

Carina Tertsakian, with the British-based watchdog group, Global Witness, says miners have few protections.

"There are no health and safety measures," said Tertsakian. "There are no precautions of any kind for the miners, who are most of the time digging with their bare hands, without any special clothing or equipment."

Patricia Feeney with the British-based NGO, Rights and Accountability in Development, says, in the absence of government oversight, and with the country still struggling to overcome the vestiges14 of its five-year civil war, which ended in 2003, tribal15 forms of ownership dominate.

"As the old state structures and controls and maintenance systems were eroded16 or collapsed17 with the war and the dying days of the [President] Mobutu [Sese Seko] period, informal ways of working these mineral-rich concessions18 have developed with no concerns for safety," she said.

Carina Tertsakian with Global Witness says that some of these former officials who took control during war years are still in control of mines, and pose another threat to miners' safety.

"They have formed gangs who are well armed and they are fighting for control of the mines," said Tertsakian.

The U.N. mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo announced this month that it is now illegal to carry weapons without authorization19 in the gold-rich Ituri province in the east, where rival militias21 vying22 for control of the mines and inter-ethnic violence have claimed thousands of lives and terrorized those who remain.

Tertsakian says that the U.N. strategy of a no-weapons mining zone is one step to increasing worker safety, but is not enough.

"It is not only a question of disarming23 militia20 groups. It is also a question of looking to see what the national army is doing," continued Tertsakian. "The governance of natural resources is still extremely weak. So, at any given time, it is quite possible that conflict over the possession and profits of these resources could resume once again."

Diamond consultant Zohar says the challenges are enormous.

"The issue comes down to corruption and good governance," said Zohar.

Carina Tertsakian says the upshot is, no one takes responsibility when accidents do happen.

"Because they are working, in theory, illegally, and because no one is responsible for them, what it means is that, when there are accidents, no one is taking responsibility for that. No one is investigating it, and no one is ensuring their basic protection," said Tertsakian .

Newly-elected President Joseph Kabila has said he will make reforming the large mineral sector one of his main priorities.

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

collapse

|

|

| vi.累倒;昏倒;倒塌;塌陷 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

primitive

|

|

| adj.原始的;简单的;n.原(始)人,原始事物 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

sector

|

|

| n.部门,部分;防御地段,防区;扇形 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

impoverished

|

|

| adj.穷困的,无力的,用尽了的v.使(某人)贫穷( impoverish的过去式和过去分词 );使(某物)贫瘠或恶化 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

corruption

|

|

| n.腐败,堕落,贪污 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

persistence

|

|

| n.坚持,持续,存留 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

oversight

|

|

| n.勘漏,失察,疏忽 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

consultant

|

|

| n.顾问;会诊医师,专科医生 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

literate

|

|

| n.学者;adj.精通文学的,受过教育的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

investors

|

|

| n.投资者,出资者( investor的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

supervisors

|

|

| n.监督者,管理者( supervisor的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

inspections

|

|

| n.检查( inspection的名词复数 );检验;视察;检阅 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

licensing

|

|

| v.批准,许可,颁发执照( license的现在分词 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

vestiges

|

|

| 残余部分( vestige的名词复数 ); 遗迹; 痕迹; 毫不 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

15

tribal

|

|

| adj.部族的,种族的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

16

eroded

|

|

| adj. 被侵蚀的,有蚀痕的 动词erode的过去式和过去分词形式 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

17

collapsed

|

|

| adj.倒塌的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

18

concessions

|

|

| n.(尤指由政府或雇主给予的)特许权( concession的名词复数 );承认;减价;(在某地的)特许经营权 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

19

authorization

|

|

| n.授权,委任状 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

20

militia

|

|

| n.民兵,民兵组织 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

21

militias

|

|

| n.民兵组织,民兵( militia的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

22

vying

|

|

| adj.竞争的;比赛的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

23

disarming

|

|

| adj.消除敌意的,使人消气的v.裁军( disarm的现在分词 );使息怒 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|