-

(单词翻译:双击或拖选)

Johannesburg

26 July 2007

A total of 19 African countries are holding multi-party elections this year, a far cry from a few years ago when many countries in Africa were dominated by single-party governments or military dictators. But quite a few elections on the continent continue to be marred1 by irregularities and administrative2 problems. Correspondent Scott Bobb reports from our Southern Africa Bureau in Johannesburg.

|

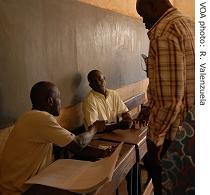

| Officials check voter cards in Mali's presidential election 29 April 2007 (VOA photo: R. Valenzuela) |

David Pottie, with the Carter Center, a U.S.-based organization that observes elections all over the world, says regular multi-party elections have become a well-established trend in Africa.

"It is somewhat less clear if the direction of that trend is actually resulting in an alternation of parties in power," he said.

The secretary-general of the Senegalese RADDHO human rights group, Alioune Tine, agrees adding that after nearly two decades of elections on the continent there is a certain voter fatigue3.

"There is the problem of confidence," he explained. "Many opposition4 parties have no confidence with the system, the regulating system, the electoral system."

Many voters say they have doubts about the independence of the bodies organizing the vote. In some countries, government ministries5 oversee6 the process, in others, electoral commissions with varying degrees of independence are placed in charge.

Denis Kadima, of the Electoral Institute for Southern Africa, says some election commissions are very independent-minded but face conditions that prevent them from operating freely.

"They may have a judiciary, which is not very independent," he noted7. "You may have the army, which may be interfering8. They [election commissions] depend on the government for funding. The party in power may also take advantage of that."

He says it is important that commissions be appointed and begin their work early, not merely a few months before the vote. And he says commission members should be replaced gradually, not all at once, so that experience is passed along to newer members.

Paul Graham of South Africa's Institute for Democracy says there are other problems.

"One is the weakness of political parties, and therefore, the sense that they don't really aggregate9 [represent] voters' interests," he said. "And they don't have a social presence between elections even if they have seats in legislature."

He says voters also face difficulties in fulfilling their role, whether in registering to vote or accessing information about the parties and their candidates.

Kadima notes that many well-run elections often end up in disputes over their results, which lead to lengthy10 legal challenges, suspicious deal-making and sometimes violence.

"Given the limited opportunities outside the state, parties or candidates tend not to accept defeat, because they know that if they are defeated they won't have access to resources," he said. "As a result, they may refuse to accept the result of a genuine, free and fair election."

Graham says this is because in Africa so much economic power lies with the government.

"Incumbency11 is in all jurisdictions12 a great privilege, but in poorer countries where the state is often seen as an area of resource, incumbency is a particular privilege," he added. "So once you are in, it's hard for people to give up power."

He adds that it is difficult for opposition politicians to establish their credentials13 because highly centralized political systems prevent them from demonstrating their leadership abilities in, for example, local politics.

And a major obstacle everywhere is a lack of resources. Experts say neither political parties nor election commissions have sufficient funds to do their jobs. Moreover, in many countries, geography, climate and poor infrastructure14 pose additional financial and logistical challenges.

Graham says these factors make African elections very expensive.

"We haven't figured how to hold cheap elections, or let's call them cost-effective elections, and develop cost effective conflict-management mechanisms," he explained.

Kadima concludes that ultimately the long-term success of multi-party elections depends on progress on broader societal issues.

"For elections to be successful, we also need over time to start addressing issues of development, because as long as we don't have opportunities outside government everyone will try to get in power by any means, including rejecting the results of a fair election," he said.

Experts note that the African Union in January adopted a Charter for Democracy, which sets out principles aimed at strengthening elections and their independence.

Each AU member is to adapt the principles to its laws and regulations. Experts say this is one more way to raise the electoral standards on the continent.

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

marred

|

|

| adj. 被损毁, 污损的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

administrative

|

|

| adj.行政的,管理的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

fatigue

|

|

| n.疲劳,劳累 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

opposition

|

|

| n.反对,敌对 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

ministries

|

|

| (政府的)部( ministry的名词复数 ); 神职; 牧师职位; 神职任期 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

oversee

|

|

| vt.监督,管理 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

noted

|

|

| adj.著名的,知名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

interfering

|

|

| adj. 妨碍的 动词interfere的现在分词 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

aggregate

|

|

| adj.总计的,集合的;n.总数;v.合计;集合 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

lengthy

|

|

| adj.漫长的,冗长的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

incumbency

|

|

| n.职责,义务 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

jurisdictions

|

|

| 司法权( jurisdiction的名词复数 ); 裁判权; 管辖区域; 管辖范围 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

credentials

|

|

| n.证明,资格,证明书,证件 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

infrastructure

|

|

| n.下部构造,下部组织,基础结构,基础设施 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|