-

(单词翻译:双击或拖选)

The French ruler Napoleon Bonaparte needed money for his war with Britain. He sold all the land drained by the Mississippi River and all its many streams for 80 million francs. Transcript1 of radio broadcast:

18 June 2008

Welcome to THE MAKING OF A NATION – American history in VOA Special English.

In our last program, we talked about two proposals by President Thomas Jefferson. Congress approved both of them. One proposal ended some taxes. The other reduced the number of judges appointed by John Adams when he was president.

In the closing days of Adams' term, Congress passed a Judiciary Act. This act gave Adams the power to appoint as many judges as he wished. It was a way for the Federalist Party to keep control of one branch of government. The Federalists had lost the presidency2 and their majority in Congress to Thomas Jefferson and his Democratic-Republican party -- known today as the Democratic Party.

Now, Tony Riggs and Shep O’Neal continue the story of America’s third president, Thomas Jefferson.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

President Adams quickly created new courts and named new judges. Just as quickly, the Senate approved them. The papers of appointment were signed. However, some of the judges did not receive their papers, or commissions, before Thomas Jefferson was sworn-in. The new president refused to give them their commissions.

One of the men was William Marbury. He asked the Supreme3 Court to decide his case.

VOICE TWO:

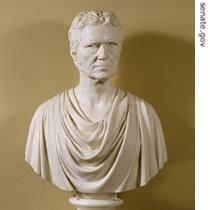

|

| John Marshall, by Hiram Powers |

The Chief Justice was John Marshall, a Federalist. Marshall thought about ordering the Republican administration to give Marbury his commission. On second thought, he decided4 not to. He knew the administration would refuse his order. And that would weaken the power of the Supreme Court.

Marshall believed the Supreme Court should have the right to veto bills passed by Congress and signed by the president. In the Marbury case, he saw a chance to put this idea into law.

VOICE ONE:

Marshall wrote his decision carefully. First, he said that Marbury did have a legal right to his judicial5 commission. Then, he said that Marbury had been denied this legal right. He said no one -- not even the president -- could take away a person's legal rights.

Next, Marshall noted6 that Marbury had taken his request to the Supreme Court under the terms of a law passed in seventeen eighty-nine. That law gave citizens the right to ask the high court to order action by any lower court or by any government official.

|

| The decision in the Marbury v. Madison case established the right of the courts to decide the constitutionality of the actions of the other two branches of government |

Marshall explained that the Constitution carefully limits the powers of the Supreme Court. The court can hear direct requests involving diplomats7 and the separate states. It cannot rule on other cases until a lower court has ruled.

So, Marshall said, the seventeen eighty-nine law permits Marbury to take his case directly to the Supreme Court. But the Constitution does not. The Constitution, he added, is the first law of the land. Therefore, the congressional law is unconstitutional and has no power.

VOICE TWO:

Chief Justice Marshall succeeded in doing all he hoped to do. He made clear that Marbury had a right to his judicial commission. He also saved himself from a battle with the administration. Most importantly, he claimed for the Supreme Court the power to rule on laws passed by Congress.

President Jefferson understood the importance of Marshall's decision. He did not agree with it. He waited for the Supreme Court to use this new power.

Several times during Jefferson's presidency, Federalists claimed that laws passed by the Republican Congress violated the Constitution. But they never asked the Supreme Court to reject those laws.

(MUSIC)

VOICE ONE:

|

| The Louisiana Purchase Treaty was signed in Paris on April 30, 1803 |

During Jefferson's first term, the United States faced a serious problem in its relations with France.

France had signed a secret treaty with Spain. The treaty gave France control of a large area in North America -- the Louisiana Territory.

Napoleon Bonaparte ruled France at that time. Jefferson did not want him in North America. He felt the French presence was a threat to the peace of the United States. He decided to try to buy parts of Louisiana.

VOICE TWO:

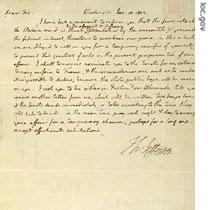

Jefferson sent James Monroe to Paris as a special negotiator.

Before sailing, Monroe met with the president and Secretary of State James Madison. They discussed what the United States position would be on every proposal France might make.

First, Monroe would try to buy as much territory east of the Mississippi River as France would sell. If France refused, then Monroe would try to buy an area near the mouth of the Mississippi River. The area was to be large enough for a port.

VOICE ONE:

|

| In this note to the newly appointed American minister to France, James Monroe, President Jefferson describes his reasons for wanting the city of New Orleans |

Monroe never had a chance to offer the American position. Napoleon had decided to sell everything to the Americans. He told his finance minister to give up Louisiana -- all of it. Napoleon needed money for a war with Britain.

James Monroe was happy to negotiate the purchase of Louisiana. They agreed on a price of eighty million francs for all the land drained by the great Mississippi River and all its many streams.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

Federalists in the northeastern states opposed the decision to buy Louisiana. They feared it would weaken the power of the states of the northeast. Federalist leaders made a plan to form a new government of those states. But to succeed, they needed the state of New York.

Vice8 President Aaron Burr was the political leader of New York and a candidate for New York governor. The Federalists believed Burr would win the election and support their plan. But Federalist leader Alexander Hamilton did not trust Burr. The two had been enemies for a long time.

VOICE ONE:

Hamilton made some strong statements against Burr during the election campaign in New York. The comments later appeared in several newspapers. Burr lost the New York election. The Federalist plan died for a new government of northeastern states.

After the election, Burr asked Hamilton to admit or deny the comments he had made against Burr. Hamilton refused. The two men exchanged more notes. Burr was not satisfied with Hamilton's answers. He believed Hamilton had attacked his honor. Burr demanded a duel9.

VOICE TWO:

A duel is a fight, usually with guns. In those days, a duel was how a gentleman defended his honor. Hamilton opposed duels10. His son had been killed in a duel. Yet he agreed to fight Burr on July eleventh, eighteen-oh-four.

The two men met at Weehawken, New Jersey11, just across the Hudson River from New York City. They would fight by the water's edge, at the bottom of a high rock wall.

VOICE ONE:

|

| Aaron Burr, by Jacques Jouvenal |

The guns were loaded. Burr and Hamilton took their places. One of Hamilton's friends explained the rules. "Are you ready, gentlemen?" he asked. Both answered "yes." There was a moment of silence. He gave the signal. Burr and Hamilton raised their guns. Two shots split the air.

Hamilton raised up on his toes, then fell to the ground. Burr remained standing12. He looked at Hamilton with regret, then left. Hamilton died the next day.

Newspapers throughout the nation reported Hamilton's death. Most people accepted the news calmly. To them, it was simply the sad end to an old, private dispute. But Burr's political enemies charged him with murder. The vice president fled to the southern state of Georgia.

(MUSIC)

VOICE TWO:

The nation was preparing for the presidential election in a few months. Once again, the Republican Party chose Thomas Jefferson as its candidate for president. But Republicans refused to support Aaron Burr for vice president again. Instead, they chose George Clinton. Clinton had served as governor of New York seven times.

The Federalist Party chose Charles Cotesworth Pinckney of South Carolina as its candidate for president. It chose Rufus King of New York to be its vice presidential candidate.

VOICE ONE:

The campaign was quiet. In those days, candidates did not make many speeches.

Republican pamphlets told of the progress made during the past four years. The former Federalist administration raised taxes, they said. Jefferson ended many of the taxes. The Federalists borrowed millions of dollars. Jefferson borrowed none. And, Jefferson got the Louisiana Territory without going to war.

The Federalists could not dispute these facts. They expected that Jefferson would be re-elected. But they were sure their candidate would get as many as forty electoral votes. The results shocked the Federalists. Jefferson received one hundred sixty-two electoral votes. Pinckney received just fourteen. Thomas Jefferson would be president for another four years.

That will be our story next week.

(MUSIC)

ANNOUNCER:

Our program was written by Christine Johnson and Harold Braverman. The presenters13 were Tony Riggs and Shep O’Neal. Join us again next week for THE MAKING OF A NATION, an American history series in VOA Special English. Transcripts14, podcasts and MP3s of our programs can be found at voaspecialenglish.com.

收听单词发音

收听单词发音

1

transcript

|

|

| n.抄本,誊本,副本,肄业证书 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

2

presidency

|

|

| n.总统(校长,总经理)的职位(任期) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

3

supreme

|

|

| adj.极度的,最重要的;至高的,最高的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

4

decided

|

|

| adj.决定了的,坚决的;明显的,明确的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

5

judicial

|

|

| adj.司法的,法庭的,审判的,明断的,公正的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

6

noted

|

|

| adj.著名的,知名的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

7

diplomats

|

|

| n.外交官( diplomat的名词复数 );有手腕的人,善于交际的人 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

8

vice

|

|

| n.坏事;恶习;[pl.]台钳,老虎钳;adj.副的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

9

duel

|

|

| n./v.决斗;(双方的)斗争 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

10

duels

|

|

| n.两男子的决斗( duel的名词复数 );竞争,斗争 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

11

jersey

|

|

| n.运动衫 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

12

standing

|

|

| n.持续,地位;adj.永久的,不动的,直立的,不流动的 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

13

presenters

|

|

| n.节目主持人,演播员( presenter的名词复数 ) | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|

14

transcripts

|

|

| n.抄本( transcript的名词复数 );转写本;文字本;副本 | |

参考例句: |

|

|

|